What does ADHD look like?

When we think about ADD or ADHD, most of us picture a hyper young boy, standing on desks, poking a classmate, and full ofenergy! Otherwise, we picture a total space cadet—a kids with his head in the clouds, who never seems to focus. However, while some people with ADHD reflect these prototypes, most do not. And while ADHD is diagnosed as a single disorder, it’s actually more of a spectrum. ADHD symptoms are expressed very differently between and within people across settings and their lifetime.

What does ADHD really look like, then? Well, there really is no actual “classic ADHD” profile, which can make it hard for kids and adults to understand their disorder and associated difficulties. But for each person, it has to do with how information gets into their brain (or doesn’t).

What does ADHD really look like, then? Well, there really is no actual “classic ADHD” profile, which can make it hard for kids and adults to understand their disorder and associated difficulties. But for each person, it has to do with how information gets into their brain (or doesn’t).

Why is there no “classic ADHD” profile that we can look to as a comparison?

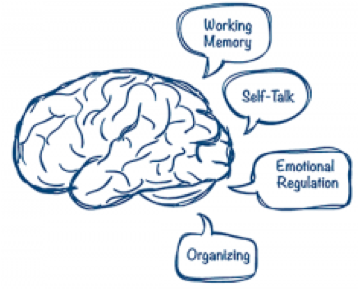

ADHD is a disorder of something called Executive Functioning, which is a group of cognitive processes largely controlled by the very front of the brain, called the Prefrontal Cortex.

ADHD is a disorder of something called Executive Functioning, which is a group of cognitive processes largely controlled by the very front of the brain, called the Prefrontal Cortex.

Those with ADHD have executive functioning deficits and, depending on which is impaired, ADHD symptoms will look different. For example, someone with an executive function of organization, will have trouble keeping organized. This includes being disorganized due to thinking on tangents, getting distracted, struggling to keep their belongings set up in ways that make life easy, and often forgetting or being scattered. On the other hand, someone with trouble inhibiting themselves also has an  executive functioning deficit. They may say things without thinking, interrupt others, touch or grab things they’re not supposed to, have big moods, struggle to control volume of voice, have lots of energy, and easily distracted by things outside of their task.

executive functioning deficit. They may say things without thinking, interrupt others, touch or grab things they’re not supposed to, have big moods, struggle to control volume of voice, have lots of energy, and easily distracted by things outside of their task.

People with ADHD often have several different executive functions that are underdeveloped for their age. As a result, it is like a “make your own sundae bar.” Everyone will end up with some key similarities (ice cream and toppings), but they will taste and look very different depending on their profile of executive functioning strengths and challenges.

What are Executive Functions?

To really understand ADHD, you need to understand executive functioning. In this section we will call Executive Functioning “EF” for short-hand. Whenever you read EF think “Executive Functioning.” Take a look at how the words Executive Functioning and EF are in purple, how the idea “EF means Executive Functioning” was repeated twice, and how it was bolded. We will come back to this later. Regardless, when you see EF, think “Executive Functioning.”

There are different metaphors people use to explain EF. The first metaphor – a sports coach. The coach is not on the court/ice/field, but the coordinator of all the plays, planning the game, and subbing players  out at times that make sense. The second metaphor – an orchestra conductor. While they don’t have an instrument, they coordinate all instruments, keep people on time, monitor how the song sounds, and coordinate what sections will be loud, quiet, fast, and slow. I like the third metaphor the best – a computer. Most cognitive processes are like the different programs on a computer. Language might be like Word, math might be like the calculator or Excel, the ability to get new information might be like the internet. Running behind all of these programs is an operating system like Windows or Safari. You never really see these operating systems in action, but when the operating system lags, the other programs don’t work so well.

out at times that make sense. The second metaphor – an orchestra conductor. While they don’t have an instrument, they coordinate all instruments, keep people on time, monitor how the song sounds, and coordinate what sections will be loud, quiet, fast, and slow. I like the third metaphor the best – a computer. Most cognitive processes are like the different programs on a computer. Language might be like Word, math might be like the calculator or Excel, the ability to get new information might be like the internet. Running behind all of these programs is an operating system like Windows or Safari. You never really see these operating systems in action, but when the operating system lags, the other programs don’t work so well.

So, what do these metaphors have in common? They all place EF as a background process that is responsible for coordinating, organizing, and monitoring the more explicit processes that are directly observable.

As mentioned above, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) – the very tip of your brain – is the main part of the brain that is responsible for EF. This part of your brain only comes to maturation at about 25 years old. This may explain why some people think that adolescents are foolish; they have adult-like intelligence, but their EF is still underdeveloped compared to their future standing in their late 20s.

There are lots of different ways to organize and think about the different EFs. One way I like is this flowchart that has different tasks or objectives as the heading and the actual EFs that contribute to the task underneath.

So, remember that sentence at the top with the purple writing and bolded letters? Let’s do a quick quiz. What does EF stand for? Hopefully you were able to recall that it stands for Executive Functioning. By making it bold and purple I reduced your demands on shifting and sustained attention. I did not expect you to automatically make the connection between EF and executive functions; instead, you were cued to purposefully remember the short hand. Here is another quiz. What does PFC stand for? If you look 2 paragraphs up you will see that it stands for prefrontal cortex. It should have been much easier for you to have remembered PFC than EF because you read it more recently and there was less distracting information in between. I am willing to bet that regardless of your performance on the “quiz,” EF was remembered more strongly than PFC. Why is that? It can’t be due to your memory ability. EF should be harder to remember than PFC because the abbreviation was introduced earlier and there were more distractors in between. However, all of the EF demands involved in encoding new information were removed. You were cued, the abbreviation was repeated, visual cues helped you shift your attention to mobilize metacognitive strategies involved in memorizing things, and you were encouraged to slow down and look at the sentence.

Because EFs run in the background, it is easy to take them for granted but they are key in almost everything in our lives.

Imagine you are asking a child to stop playing videogames to go do their homework without kicking up a fuss. The following EFs are required: inhibition of emotion (feeling upset about having to stop), inhibition of behavior (not complaining or making a fuss), shifting attention away from the game to homework, perspective taking (person wants me to do it), organization of  school materials, initiation of a new activity, regulating energy level (high arousal videogame to low arousal homework), and metacognitive awareness (remembering that I care about homework because I want to achieve a goal or avoid a consequence)…all of this ON TOP of the fact that they probably don’t want to do homework and are just doing it because the adult wants them to AND the work itself might be hard and annoying. The more that you can reduce EF demands the easier that this transition will be.

school materials, initiation of a new activity, regulating energy level (high arousal videogame to low arousal homework), and metacognitive awareness (remembering that I care about homework because I want to achieve a goal or avoid a consequence)…all of this ON TOP of the fact that they probably don’t want to do homework and are just doing it because the adult wants them to AND the work itself might be hard and annoying. The more that you can reduce EF demands the easier that this transition will be.

EFs are trainable in much the same way that math and language are trainable. You just need to remember that because ADHD is a disability in EF, the gains in EF will be slower and less than for a neurotypical person. So it’s important to be really patient with  your child with ADHD. There is a limit to how much Executive Functioning people can develop and this limit increases with age until our mid to late twenties.

your child with ADHD. There is a limit to how much Executive Functioning people can develop and this limit increases with age until our mid to late twenties.

To learn more about ADHD, Executive Functioning, or learning how to manage related difficulties, contact a mental health professional in your area.

Dr. Eli Cwin, Clinical Psychologist (Supervised Practice)

Family Psychology Centre