Amid a second wave of the global Coronavirus pandemic in Canada, shoppers are hitting the stores to stock up on the limited supply of toilet paper, canned goods, and cleaning agents…where they can find them. With case numbers increasing daily and a current total of 481,630 confirmed cases in Canada (Government of Canada, 2020), shoppers are taking every opportunity they can to clear the shelves for essential items. With a full lockdown looming, have you done your big shop yet?

How are you feeling after reading that just now? Fearful? Panicked? Pressured to do that shop? This was written intentionally to demonstrate how engaging in media can influence one’s emotions. By beginning this article in such a negative way, I have highlighted how mass media has a tendency to consistently emphasize some of the worst potential outcomes of this pandemic, such as running out of resources and materials we need to keep safe. In doing so, this can promote unsettling thoughts, fear, and panic surrounding the progression of this virus. However, before we panic buy all those 24 packs of toilet paper, let’s consider the facts. While there are no current food shortages at grocery stores, and only some restrictions on cleaning supplies, why all this panic buying?

The media has also done its job to keep us informed and knowledgeable about how the virus works, encouraging us to be more cautious with our social interactions and outings, limiting trips, and buying only what we need. However, the continuous overexposure to empty shelves, public announcements to stay home, and scary statistics seen in daily news may foster a repetitive environment of negativity, tricking our brains into thinking that we need to engage in these panic-like behaviours. Consequently, this motivational drive to buy due to repeated exposure of negative news may be based on a decision-making phenomenon known as “availability heuristics” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

Scientists have described availability heuristics as seeing something over and over again, making us think that concept or idea is true (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). For example, suppose your favourite TV network has a shark week and plays movies like Jaws several times. Being quarantined like everyone else, you decide to binge-watch them. Now let’s say your family wants to take a trip to the beach in the near future. After watching these movies, you might find yourself judging your risk of being attacked by a shark so great that you plan to avoid any encounters with the beach. This judgement of having an increased risk of being victim to a shark attack, solely based on your media exposure through the movies, is exactly what the availability heuristic does to affect your decisions. In fact, numerous studies have demonstrated that people tend to make more errors when they rely on this misguided decision-making method, leading to both societal and personal costs (Ceschi et al., 2019; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

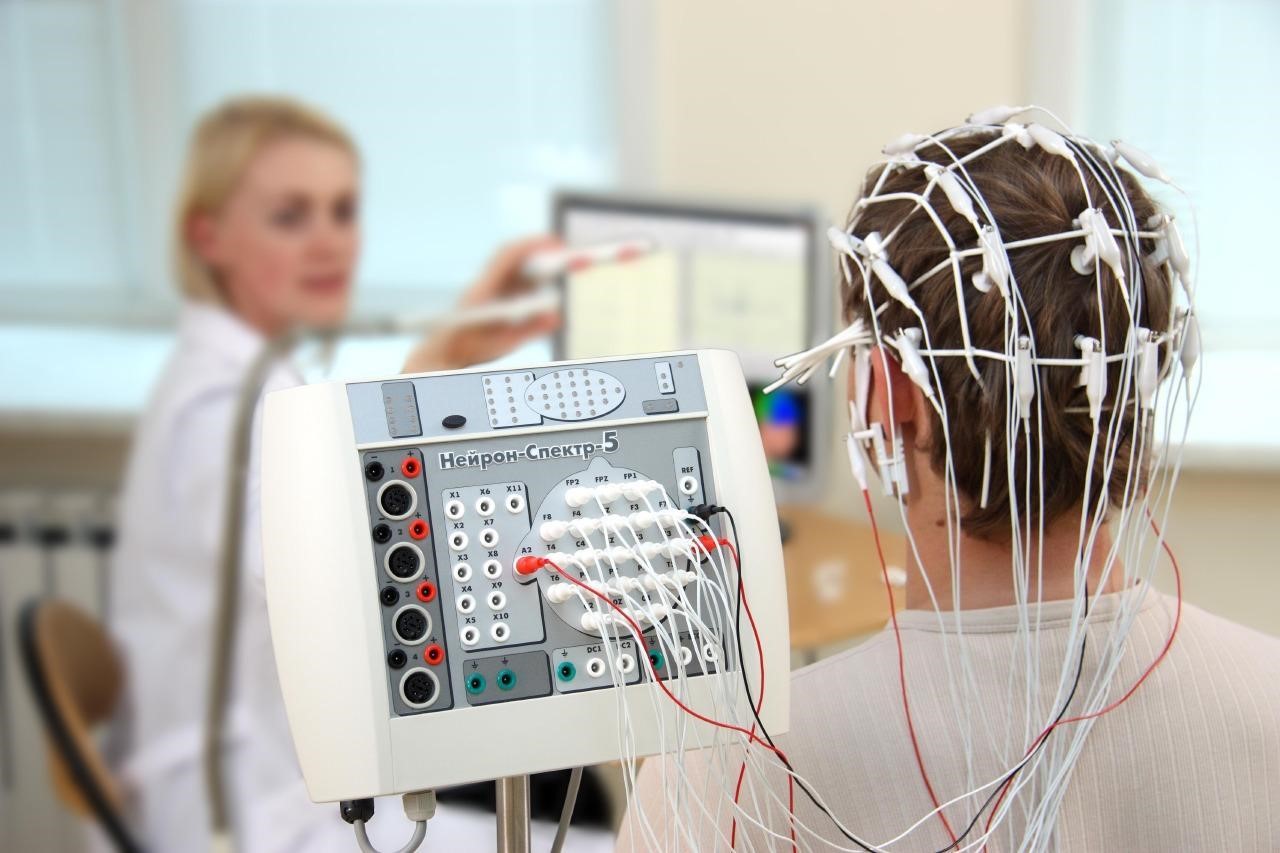

Interestingly, it’s been noted that using these types of error-driven judgements can result in changes to our brain activity! In 2017, a study was conducted on decision making using a brain-scanning technique known as Electroencephalography (EEG), wherein multiple electrodes are placed over the scalp to detect brain waves changes. Researchers looked for differences between people who rely on more thoughtful, slower decision- making strategies and those who use the quick, heuristic-based ones, which were previously described (Wichary et al., 2017). When completing a decision-making task using cues to infer how expensive two diamonds were, the researchers found that individuals who relied on the thoughtful decision strategies considered more cues, like shape and colour, before making a decision. On the other hand, those who used the quick decision strategy appeared to only consider the first cue (Wichary et al., 2017). As such, heuristic users showed less activity in a brain signal, known as P3, which was higher in the thoughtful strategy group, who considered multiple attributes of a choice before making a decision (Wichary et al., 2017). In combination with a reduced ability to make reasonable and informed decisions (Levine, 2009; Wichary et al., 2017), heuristics users also show increased activation of a brain region known as the amygdala, which is largely involved in processing negative emotions such as fear (Levine, 2009; Ressler, 2011).

So, how exactly does this dependency on availability heuristics lead to panic buying? Well, by using this strategy to make ill-informed decisions, we become more susceptible to the influence of our own fear. The repeated media presentations of empty shelves, the long grocery lines, and even the unending length of this pandemic can put us at a high risk of developing a motivational ‘drive-to-buy’ to avoid “losing out”, known as “loss aversion” (Kahnman & Tversky, 1979). This fear-based buying is exactly what we have been seeing in the news with common pantry items such as toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and even pasta.

It appears that our over-exposure to unfortunate updates about the Coronavirus from media sources could be harmful; promoting quick judgements in shoppers to engage in panic buying to avoid a false resource shortage. When in reality, this decision-making behaviour has the potential to produce the shortage we are afraid of. Thus, how can we overcome this flawed way of thinking? Primarily, staying accurately informed and buying only what you currently need is the best way to prevent a resource shortage. Additionally, reinterpreting the way we see news about COVID-19 by focusing on positive aspects is a supported cognitive technique to reduce the fear of loss aversion. For example, the media has contributed optimistic commercials, reminders, and tracking apps to keep us informed about the virus, ensuring we know how to keep ourselves and our loved ones safe. Media has also made us feel more comfortable wearing masks in public and keeping distance from others, socializing people to this new norm and reducing the fear of appearing rude or anti-social, respectively. We have also been exposed to some truly amazing stories of frontline workers and their efforts towards taking care of our loved ones or otherwise. With the current mass coverage of prospective, accessible vaccines in the near future, the media has provided another optimistic outlook towards getting this virus under control.

While some of the topics covered in the media may make us nervous through repetitive and sometimes unsettling reports, focusing on the informed, health-conscious updates will help in reducing such fears. By practicing the recommended safety measures, we can work together as a team to support one another and ensure this viral episode is cancelled.

References

Ceschi, A., Costantini, A., Sartori, R., Weller, J., & Di Fabio, A. (2019). Dimensions of decision-making: An evidence-based classification of heuristics and biases. Personality and Individual Differences, 146, 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.033

Government of Canada. (2020, April 5). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update. Government of Canada. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html#a1

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Levine, D. S. (2009). Brain pathways for cognitive-emotional decision making in the human animal. Neural Networks, 22(3), 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2009.03.003

Ressler, K. J. (2010). Amygdala Activity, Fear, and Anxiety: Modulation by Stress. Biological Psychiatry, 67(12), 1117–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.027

Tversky, A., Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science (New York, N.Y.), 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Wichary, S., Magnuski, M., Oleksy, T., Brzezicka, A., & Wichary, S. (2017). Neural signatures of rational and heuristic choice strategies: A single trial ERP analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 401–401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00401